- 1-833-448-3843 Make a call.

- info@givetouhf.ca Drop us an email.

- We are located in Edmonton, Alberta

Last chance

Dr. Gurmeet Singh gives hope to patients who are minutes away from death.

Dr. Gurmeet Singh gives hope to patients who are minutes away from death.

Though she was moments from losing consciousness, Jolissa Doerksen grasped the severity of her situation. Lying immobile in a hospital bed in Grande Prairie’s intensive care unit, the 23-year-old new mom was alternating between seeing bright light and blackness.

“I felt my body was shutting down, faster and faster. I was starting to think, ‘This is it, I’m going to die. I’m done,’” she says of that terrifying day in May 2014.

“I said to myself – only to myself – ‘I’m dying, I know I’m dying.’ The only thing I could do was pray that I would make it through, because my husband and my baby still needed me.”

As she teetered between life and death, another thought crept in. “I felt in my heart, ‘It’s not your time yet. You’re not ready to go.’”

It’s one of the last thoughts she remembers before she blacked out.

It turned out that last thought was correct. But it would be 12 days and a stint on Alberta Health Services’ (AHS) Mazankowski Alberta Heart Institute (Maz) with cutting-edge life-support technology before Doerksen would wake up again. Doerksen didn’t know it at the time, but her body was in the deadly grip of hantavirus, which she caught from unknowingly inhaling deer mouse droppings while cleaning out her family’s holiday trailer at their home near Fort Vermilion, Alberta.

A rare infection, in its final stages, hantavirus causes the lungs to fill up with blood and other fluids. At its most severe, the only possible way out is mechanical life support.

By the time she arrived at AHS’ Maz, Doerksen was at that point. There was some doubt over whether she could survive the flight from Grande Prairie to Edmonton, but doctors decided her only shot at survival was right here.

Her husband, Jerry, made the trip by car. When Jerry reached the hospital, recalls Doerksen, he was frantic.

He ran up to the first doctor he saw, pleading for information about his wife. The doctor told him, “We just put her on life support. I think she’s going to make it.”

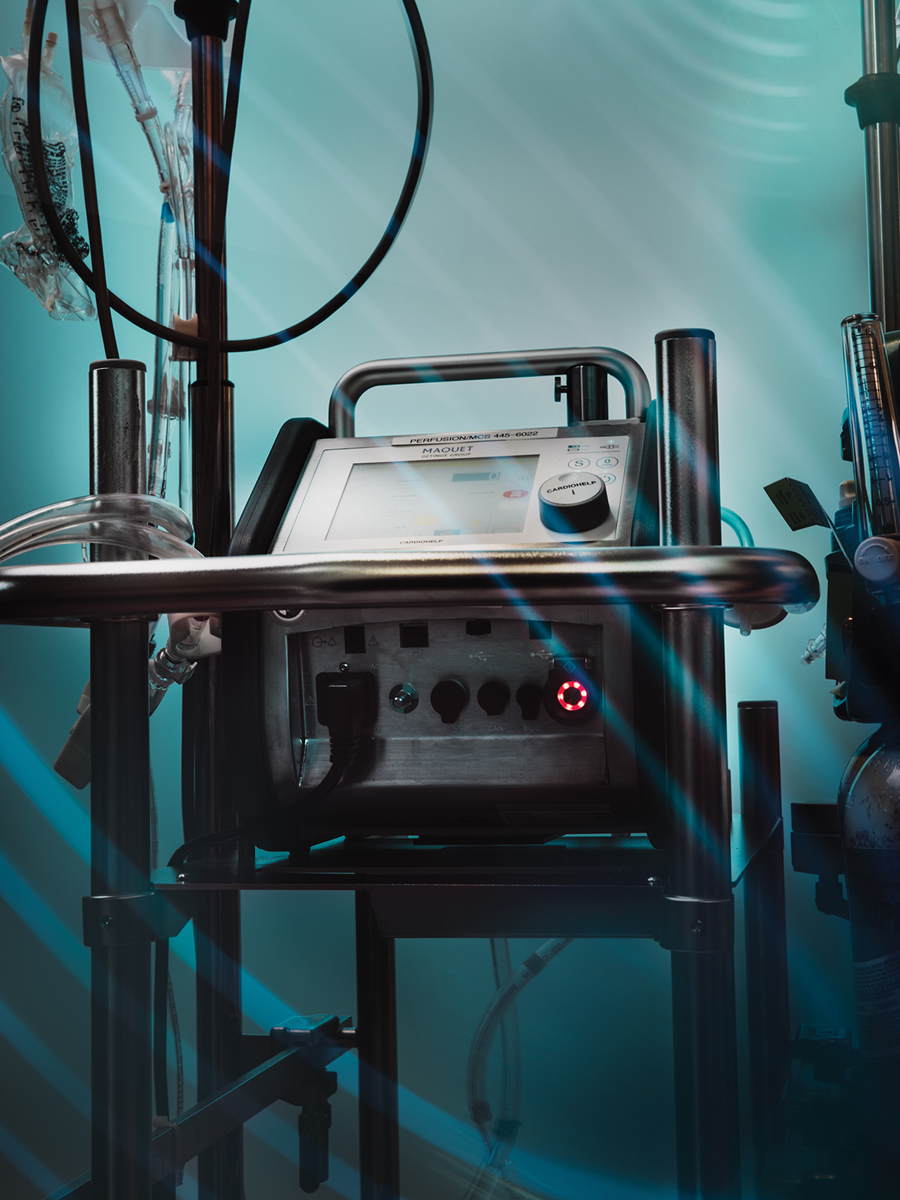

Mechanical life support called extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO for short) assumes the function of the heart and/or lungs. “It is a heart and lung machine at your bedside – that’s the simplest way to describe it,” says Dr. Gurmeet Singh, the medical director of the Adult ECMO program at the Maz.

Once placed on ECMO, the patient’s blood is drawn out of his or her body and pumped into an artificial lung, which removes carbon dioxide from the blood and adds oxygen. The freshly oxygenated blood is returned back into the patient.

Patients who need ECMO are the sickest of the sick, facing anything from life threatening lung infections to shock due to severely impaired heart function. Doerksen was on ECMO for 12 days.

“These patients require more support than a ventilator or medication. They’re often on the precipice of multi-organ failure, if they don’t already have it. They’re hours to minutes from death,” says Singh.

Generous community support to the University Hospital Foundation, including callers to the 630 CHED Heart Pledge Day in 2017, an annual day-long fundraising event at the Maz, have donated over $700,000 for the purchase of the most advanced ECMO equipment, including portable machines that make transporting patients for imaging or even surgery immeasurably easier.

“We are eternally grateful for the support we’ve received that’s allowed us to have this equipment on hand when we need it,” says Singh. “There is no other option for these patients. This is it.”

The life support team at the Maz is multidisciplinary, comprising everyone from those like Singh, an intensivist and cardiac surgeon, to other surgeons, perfusionists, anesthesiologists, OR nurses, ECMO specialists and so on.

“The success of any program is completely dependent on the members of the team – the people who are dedicated to the program’s success,” Singh says.

“By volume we are probably the second-biggest program in the country” after Toronto, says Singh. “I have worked in four advanced cardiovascular intensive care units across North America, including the Cleveland Clinic, and I can tell you that our program is second to none, anywhere in the world.”

The number of patients who go on ECMO has climbed from 15 to 20 a year when Singh came to Edmonton 12 years ago, to about 50 per year now, though the peak was 70 in a year. Prior to 2009, ECMO support was not offered for isolated lung failure. Even so, Singh and his team only accept a percentage of the ECMO referrals, as many just will not benefit from this type of support.

“We’re aggressive, but there’s no bravado,” says Singh. “We say, ‘Call us for everything.’ We want to know what’s out there, because as long as we know what’s out there, there’s less danger we’re going to miss someone who can be helped.”

It’s crucial to note that ECMO is always a “bridge” to another end point, whether that eventuality is recovery, an organ transplant, or a decision to turn life support off.

For Doerksen, of course, ECMO was a bridge to recovery. She believes she wouldn’t be alive today had ECMO not been available for her. More than three weeks after her ordeal began, she was reunited with her baby daughter. And though she has a few lingering health effects, such as sore feet and weakened lungs, she went on to have two more children.

“We are so incredibly lucky here in Alberta to have access to absolutely amazing life-saving technology. There’s no question that it saves lives,” she says, adding she’s thankful for every medical professional who cared for her.

“They all played a part in my miracle.” Doerksen’s case is just one of the positive stories Singh has collected during his 12 years at the hospital. True, there can be a harsh reality to life support, and some patients don’t get better – but many do.

One day, Singh was at work when a young woman, a hospital porter, approached him.

What she said surprised him, as he hadn’t known that one of his patients, who had been on ECMO during a severe bout with H1N1 flu, had a family member working at the hospital.

“She stopped me in the hallway to thank me for saving her dad,” says Singh, emotion in his voice and some extra moisture in his eyes as he recalls the encounter. “There are so many gratifying stories, these patients and their resiliency are constantly redefining my expectations.”